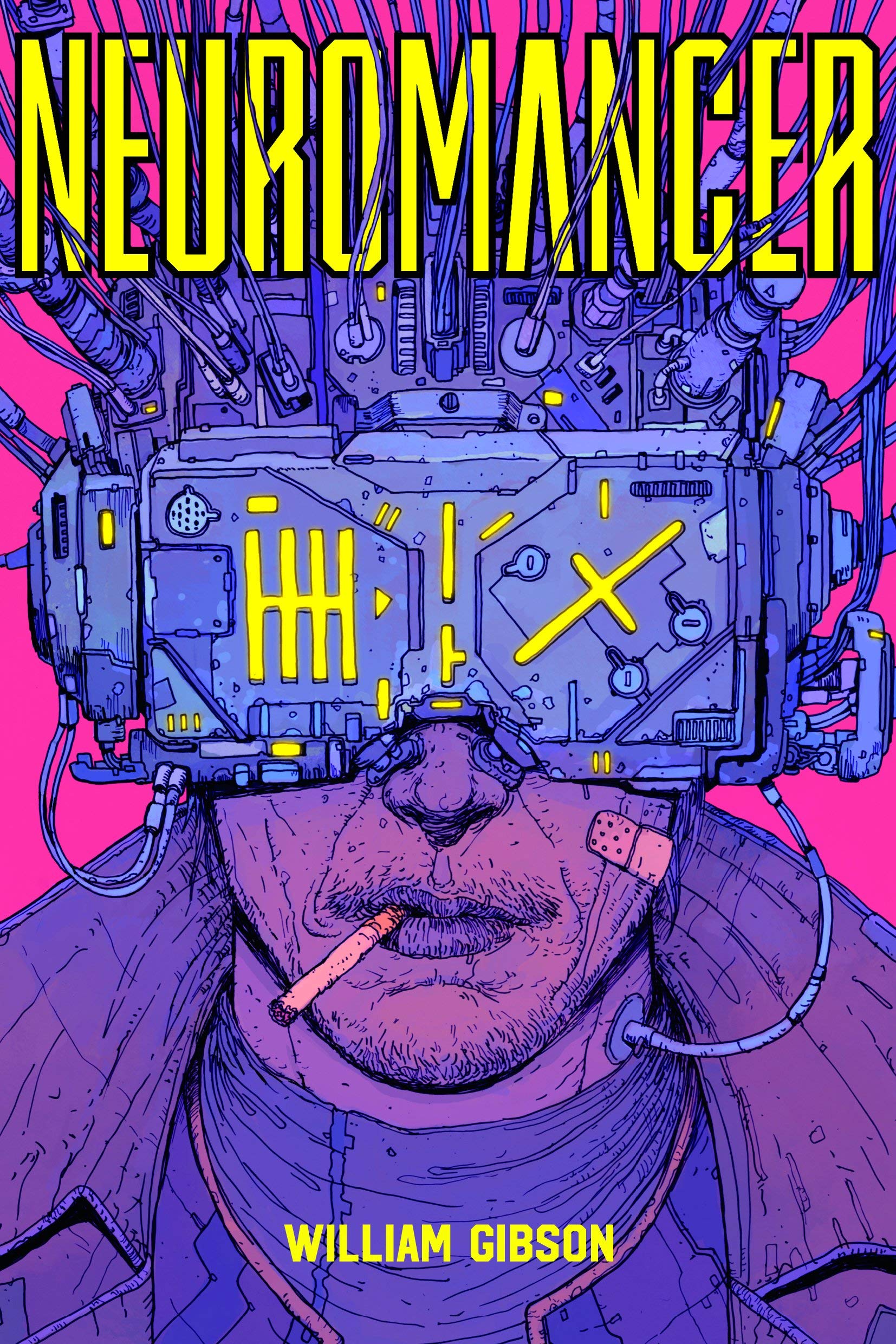

Picture this: it’s 1984, the year of Ghostbusters, The Terminator, and legwarmers. Then along comes William Gibson, a guy who basically looked at the future, shrugged, and said: “Yeah, it’s going to be neon, corporate-owned, and filled with hackers jacked into cyberspace.” And the kicker? He wasn’t wrong.

Neuromancer didn’t just define cyberpunk. It built the neon-soaked blueprint. Without it, we wouldn’t have The Matrix, Blade Runner 2049, or half the techno-babble in every sci-fi RPG you’ve ever played. Gibson gave us the vibes, the lingo, and the paranoia long before Wi-Fi was even a thing.

Cyberspace Before the Internet Was Cool

Gibson literally coined the word “cyberspace.” At a time when most people thought computers were glorified calculators, he imagined a digital frontier people could jack into like a drug. Forget dial-up tones and floppy disks. Gibson skipped ahead to a global network of virtual landscapes, corporate espionage, and data cowboys.

And here we are, four decades later, living in a world where we carry tiny supercomputers in our pockets, argue with strangers on Twitter (sorry, “X”), and let corporations track our every move. Gibson basically predicted your smartphone addiction before Snake was even a game.

The Hacker as Anti-Hero

Case, the novel’s protagonist, isn’t your typical hero. He’s not noble, not particularly kind, and his life choices scream “please don’t follow my example.” But that’s the point. In a genre obsessed with systems of control, the hacker-anti-hero is the perfect rebel.

Case isn’t saving the world; he’s just trying to get his neural implants fixed so he can dive back into cyberspace. And yet, his very existence, flawed and desperate and stubborn, resonates with anyone who has ever felt like a cog in a machine too big to fight.

Mega-Corporations, Mega-Problems

Cyberpunk has always been less about chrome arms and more about who owns the chrome factory. In Neuromancer, corporations don’t just run the show. They are the show. Governments are practically background noise.

Sound familiar? Between tech giants swallowing entire industries, data breaches leaking your most embarrassing passwords, and billionaires casually aiming for Mars, Gibson’s dystopia doesn’t feel so far-fetched anymore.

Style That Stuck

You know a book has cultural staying power when its language becomes shorthand for an entire aesthetic. “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” That opening line still slaps, decades later. It’s gritty, it’s weirdly poetic, and it tells you everything you need to know about the world you’re entering.

That grimy-future-meets-poetic-noir tone has become the voice of cyberpunk. Everyone from game designers to filmmakers has borrowed it. Often poorly, sometimes brilliantly, but always with Gibson’s fingerprints all over it.

Why It Still Matters

The genius of Neuromancer isn’t just in predicting tech. It’s in predicting the relationship between tech and people. Gibson saw how we would trade privacy for convenience, how corporations would wield more power than politicians, and how humanity would still be messy, broken, and yearning even in a world of infinite digital dreams.

Cyberpunk isn’t about shiny gadgets. It’s about the cracks they expose. And that’s why Neuromancer still defines the genre today. It’s less a prophecy and more a mirror. A distorted, neon-lit one, sure, but a mirror all the same.

Final Thought

If you’ve never read Neuromancer, do yourself a favor: grab a copy, pour yourself a strong coffee (or something stronger), and prepare to be confused by jargon that didn’t exist when it was written. Half the fun is realizing Gibson made up tech slang that we actually went and built. The other half is realizing just how close we are to living in his dystopia.

And hey, at least the legwarmers didn’t make a comeback. Yet.